The last article addressed the issue of the role that political stability plays in ensuring economic stability. We saw how unstable political systems made of internally belligerent political parties negatively affect economy. As toxic dynamics of reciprocal vetoes on the complex of measures to be enacted in order to get the system going obstruct the mechanisms of decision making.

However, the issue remains of how to ensure political stability. Let us start by saying that nations’ culture is key in determining the role that political stability plays.

Generally speaking, Anglo-Saxon countries such as the UK and the US favour political stability over representativeness, especially when representativeness entails a higher level fragmentation of the political system.

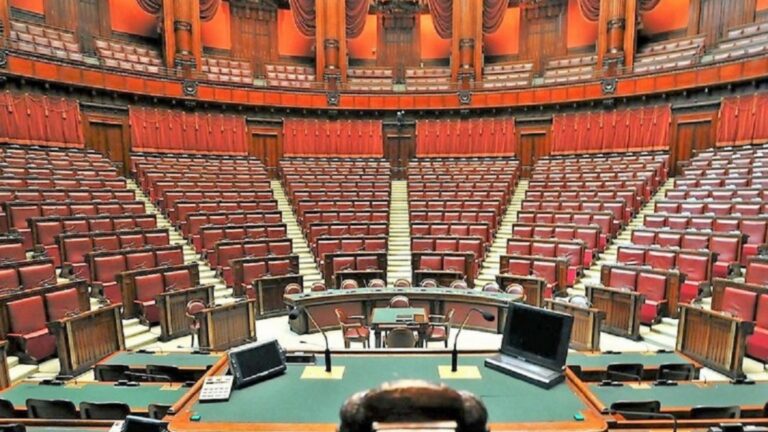

On the contrary, in countries such as Italy representativeness is worth more than political stability, even if this entails extreme forms of political fragmentation that are detrimental to decision making processes. As a consequence of such level of fragmentation, since 1946 Italy has changed 67 governments and 44 prime ministers. Such shifts and changes in the composition of parliamentary majorities deeply affected the capacity of the country to embark in thorough programs of reforms – which also undermined its financial credibility and stability.

Germany and France, on the other hand, managed to successfully reach a steadier balance between representativeness and stability, thus guaranteeing durable governments.

All this entails the issue of the electoral law. The US and the UK have majoritarian electoral systems that ensure certainty about who wins the elections. The party who gets the majority of votes is the party that designates the government and the person in charge of it.

Yet, in the UK neither the Conservative Party, nor the Labour Party, nor the Liberal Party were able to win and absolute majority in the Parliament in the 2010 elections, so that it was necessary to form a coalition government between liberals and conservatives – which was a rather unusual outcome for a country so much committed to the idea of stability and clear alternation in power.

Germany’s parliament is instead elected according to the principle of proportional representativeness. Nonetheless the high threshold needed to enter the parliament, guarantees the formation of rather stable majorities.

The lack of such a threshold in Italy produced a high level political fragmentation which resulted in no political, hence government stability. In the early 1990s this changed. The 1994 parliament was elected according to a majoritarian law (named Mattarellum after Sergio Mattarella, the current President of the Republic), which introduced a bipolar criterium, hence a much higher level of political stability. In fact, the majority of seats in parliament were distributed according to a majoritarian criterium, while just a minority of seats were assigned according to the proportional system.

This changed again in 2005 as the Porcellum (Pig) was issued. This law was designed by Roberto Calderoli (Northern League), who he himself said it was “rubbish”. The Chamber and the Senate were to be elected according to two different systems of seats distribution. The existence of a majority bonus acknowledged in the Senate to the party or the parties coalition which would win the majority of the voting constituencies in the regions resulted in the election of two different majorities in the Chamber and the Senate. The law was later deemed unconstitutional by the Constitutional Court. The latest law (the Rosatellum, named after Ettore Rosato) distributed 61% of seats according to a proportional system and led to the current unstable situation.

The political debate in Italy has recently been focusing on whether to recover the majoritarian system or keep the proportional system. It is quite peculiar that Democratic Party’s politicians and a number of centre left journalists, who until not so loge ago stood in favour of the majoritarian system, now claim that the return of this latter would lead to the victory of the Northern League and Fratelli d’Italia – the far right, populist party whose leader is Giorgia Meloni. And that it would be better to discard it from the agenda of political reforms.

Politics is not just about managing the here and now, but is about thinking, shaping and building the future for the generations to come. We are all aware of the damages caused by political fragmentation. Still, it appears that instead of focusing on how to tackle fragmentation between adversarial groups both within the single parties and coalitions, what needs to be done to ensure what is good for the country both now and in the future (an electoral law to be able to guarantee stability) is sacrificed on the altar of short term political convenience.

We either believe or do not believe in the democratic processes and procedures. A political party which aims at governing a country and gaining not just political, but cultural hegemony, cannot turn its back to necessary reforms just because such these might lead to an opponent’s victory.

Antonio Desiderio